A Brief History

of Time

Read more >

From Industry to Art – Hard Hat Tour Film by IMPATV

Commissioned thanks to the National Lottery Heritage Fund and created by our very own IMPATV, ‘From Industry to Art’ digs deeper into the fascinating history of the Islington Mill building. The film explores the Georgian building techniques used and the building’s history as a cotton spinning mill, in addition to the roots of Islington Mill Arts Club and the space we know today.

1793 & 1806:

Mills and gas lights come to Chapel Street

The Phillips Wood & Lee Cotton Twist Mill was one of the very first mills built in Salford, in 1793, on a site between Chapel Street and the River Irwell. Later on in its lifespan the mill innovated the use of gas lamp lighting, which extended onto Chapel Sreet itself, making it the first location for such lighting in the world.

“[O]n 1 January 1806 the mill together with a part of Chapel Street were lit by gas, the first recorded use of gas for street lighting anywhere in the world.”

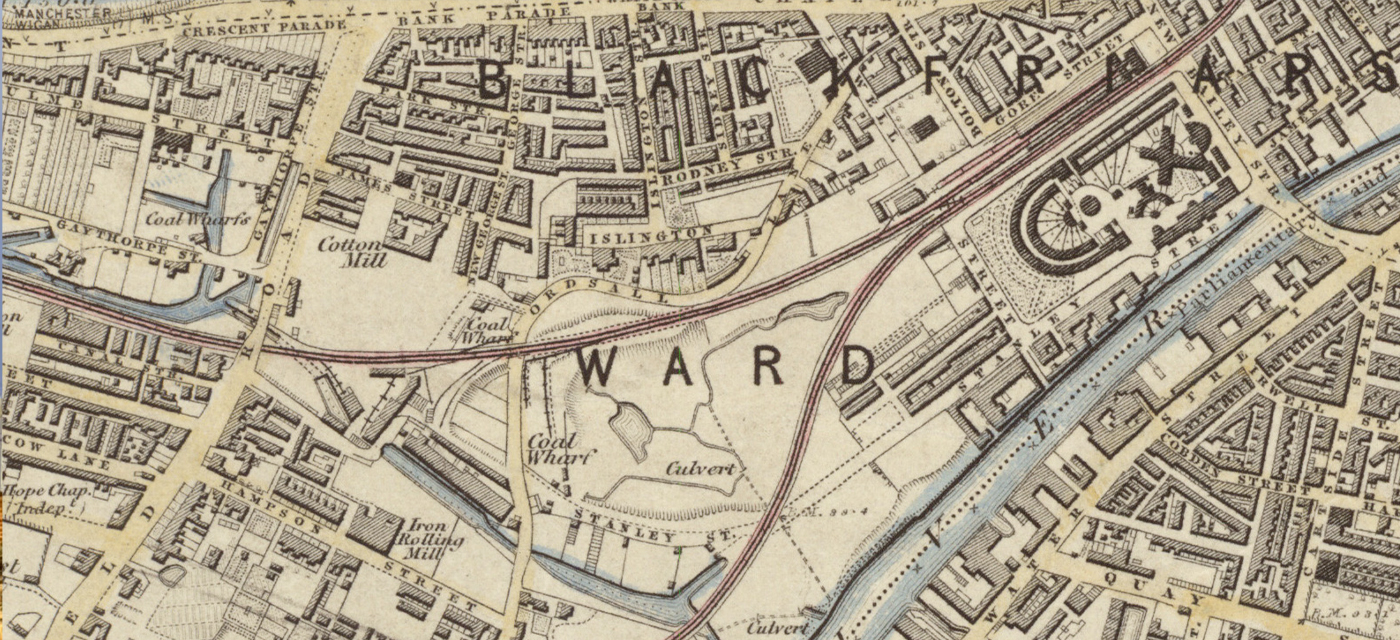

A map of Manchester from 1801. The green space to the South-West of New Bailey is where Islington Mill will later be built.

1819:

Peterloo

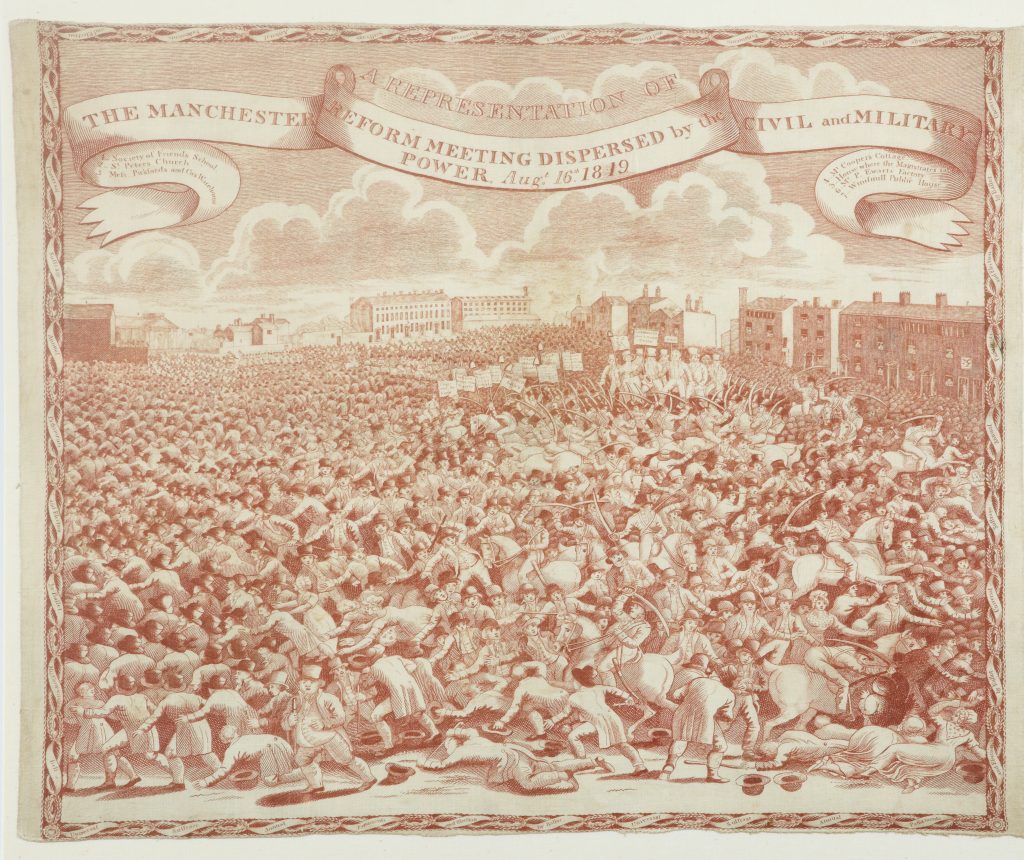

Read about The Peterloo Handkerchief (pictured above) at The People’s History Museum at this link.

The Peterloo Massacre of 1819 would still have been a raw and recent memory when Islington Mill was constructed in 1823. On 16 August 1819 a peaceful meeting of 60,000 people, united against poverty and exploitative working conditions, gathered at St Peter’s Fields and were soon met with military violence which left 18 innocent people murdered and around 700 seriously injured.

The Peterloo Memorial Campaign hosts a list of those involved (see this link), several of whom resided on Gravel Lane, where Islington Mill worker Susannah Hambleton also lived at the time of her death in the collapse of Islington Mill. 18 people also died in that terrible incident. You can read more about the collapse and our commemoration of the event at numerous links on our main Heritage page.

The University of Manchester hosts an extensive digital collection relating to Peterloo. Click this link to find out more.

In 1820 George IV succeeded George III as the King of England.

At that time Salford was part of the county of Lancashire (and remained so until 1974). The construction of Islington Mill in 1823 means that our heritage is that of a Georgian Lancashire cotton mill, one of the very few of its kind still remaining, and distinct from the Victorian mills that would come to dominate the landscape of the two cities.

1823:

Islington Mill is born

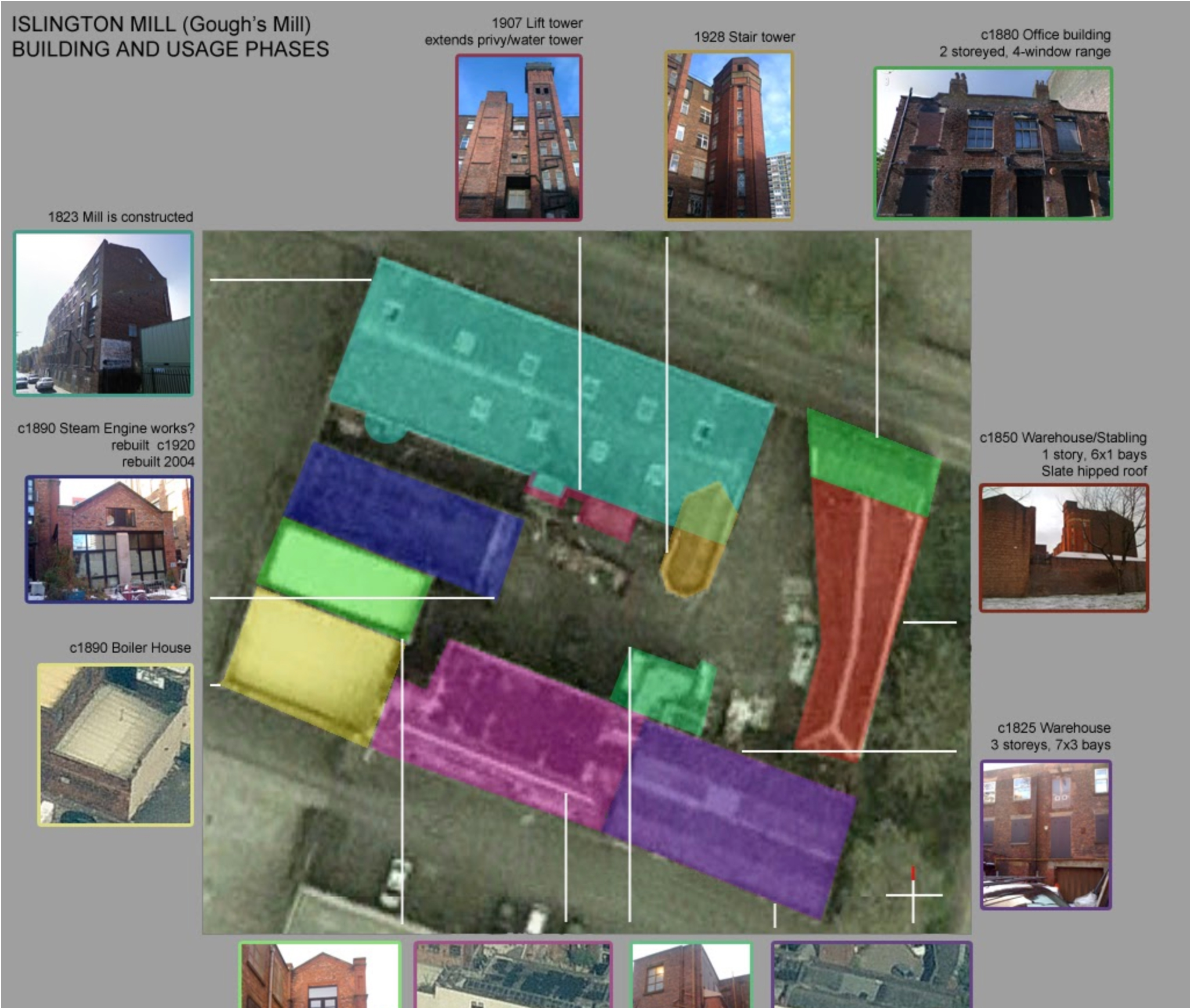

“A seven storey mill, twelve bays long, internal beam engine house with upright drive shaft to each floor. On the south side a water tower and extension have been added. An early fire-proof mill constructed in 1823 by the building firm of David Bellhouse, responsible for a number of Manchester’s early mills. Near the terminus of the Manchester, Bolton and Bury Canal. Built as a room-and-power mill, which was tenanted to persons involved in cotton spinning.”

– R. McNeil and M. Nevell (2000), A Guide to the Industrial Archaeology of Manchester

Salford Cross in 1820. (Image courtesy Victorian Web).

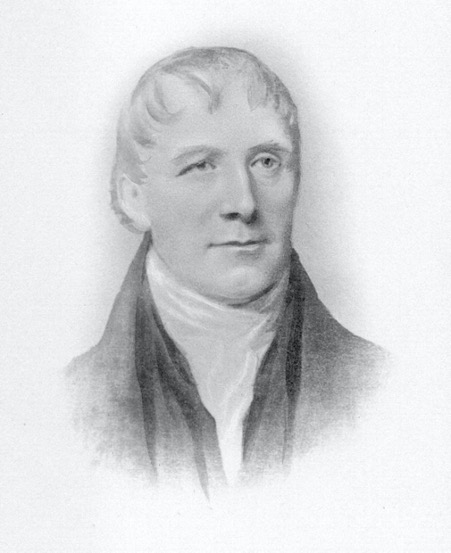

David Bellhouse, the architect of Islington Mill.

Islington Mill was originally built for cotton spinning in 1823 by the self-taught Leeds-born architect David Bellhouse (1764–1840) for Nathan Gough. Bellhouse’s firm was also responsible for the construction of the Manchester Portico Library, of which Bellhouse was also a founding member, and the original Manchester Town Hall which resided on King Street, designed by Francis Goodwin, and later demolished.

1824:

The mill collapses

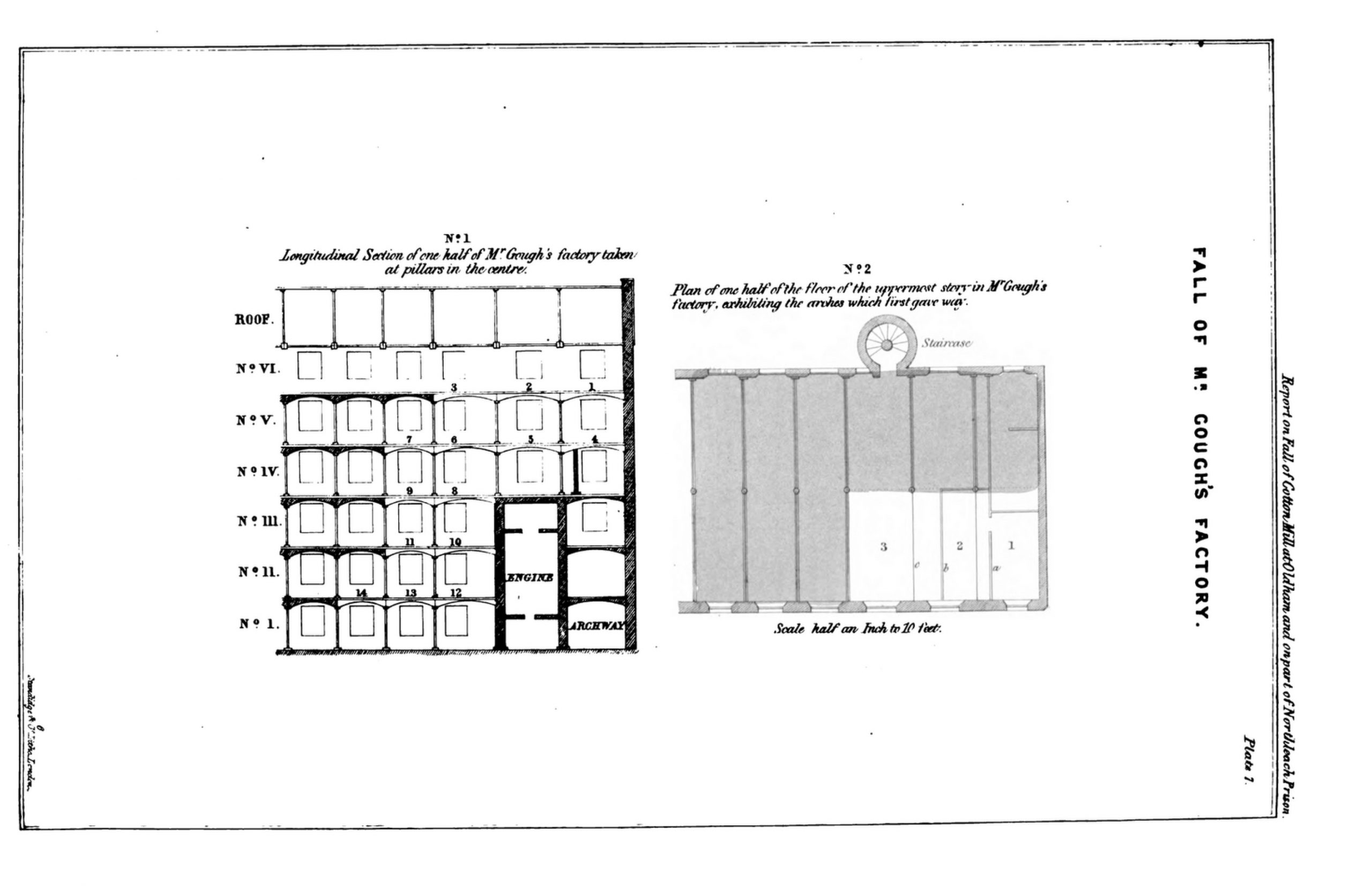

Just one year after Islington Mill was built there was a structural collapse of the building when a supporting cast iron beam broke. The floors of the building partially collapsed, one into the other, trapping workers amidst “bricks, slate and fragments of machinery”.

People leapt from windows to escape. Eighteen people were tragically crushed to death. Three of those were boys and the rest were young women and girls who made up the bulk of the mill’s workforce.

Witnesses in the area reported a “cloud of dust which obscured the air” amidst intense pandemonium and distress.

An 1845 Parliamentary paper addressed the collapse of the building and featured an architectural drawing and extracts from the original Manchester Guardian coverage of the incident. An extract is shown above.

You can also view a contemporary report of the tragedy from The Portfolio of Entertaining and Instructive Varieties (October 1824) at this link.

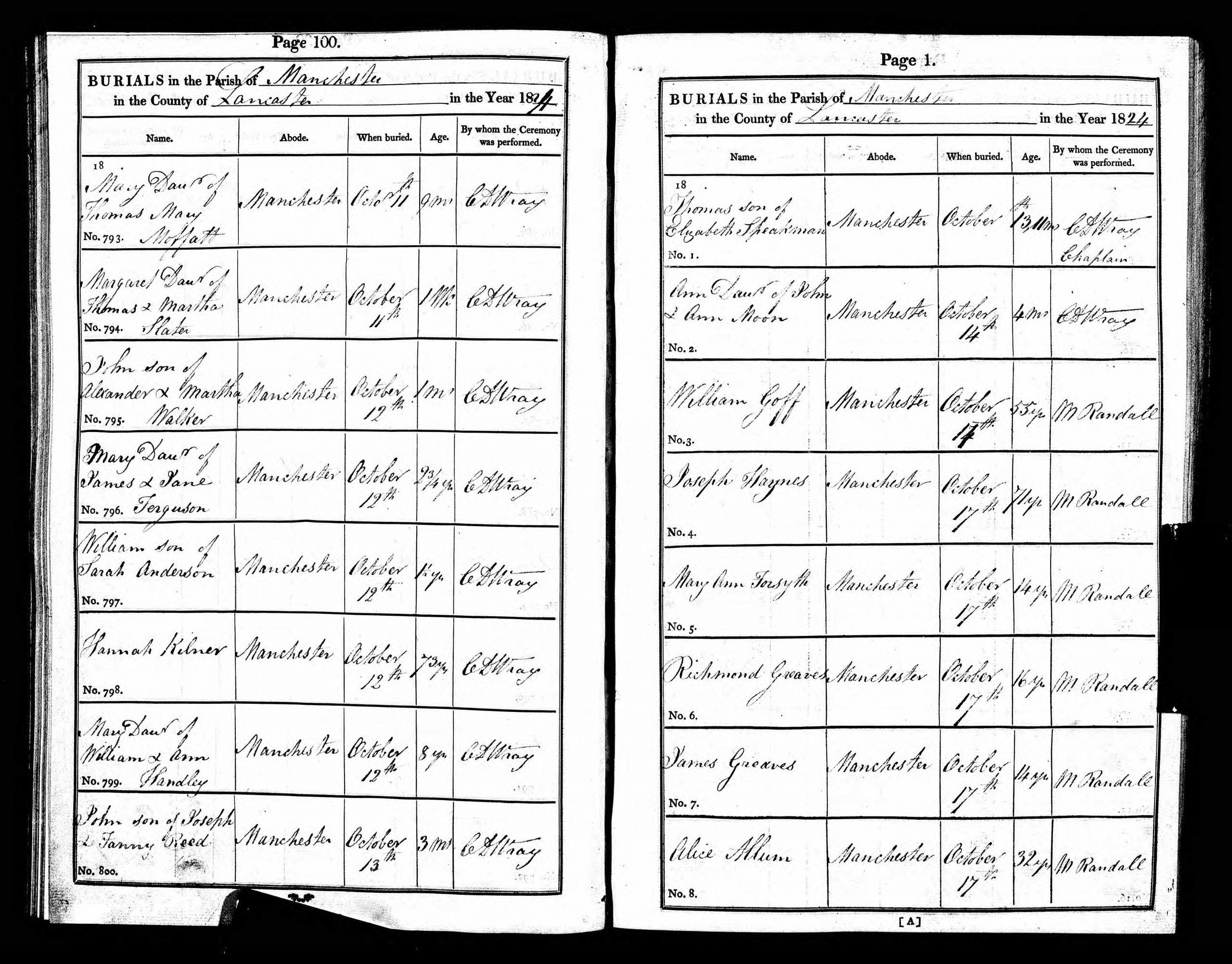

This image shows a burial record containing the names of four Islington Mill workers: Mary Ann Forsyth (aged 14); Richmall Greaves (misspelled as ‘Richmond’, aged 16); James Greaves (aged 14); Alice Allum (aged 32).

In 2021 we undertook a research project to verify the identity of the workers. Half of the original memorial list contained errors in either name, age or both. We now have verified records for 15 of the 18 dead. You can read an essay about the research project here. This page summarises our research including numerous artist commissions based on the tragedy.

1824: The mill is re-built

The mill’s original structure had consisted of a single row of cast-iron columns. During the rebuilding, additional rows of support columns were added for structural strength. The re-opened mill was in use for cotton spinning and later for doubling.

The new structure is said to have influenced the design of subsequent mill buildings and there is also an oft-quoted rumour that the architectural structure of the mills of the North West inspired the budding skyscraper builders of Manhattan. We are digging for evidence of this.

1830s onwards: Expansion

It seems that throughout the 1830s at least the mill was known as “Gough’s cotton mill” and is listed as Nathan Gough’s address in a contemporary advertisement.

Meanwhile the area of Salford in which the mill stood was a truly dismal example of Victorian industrial poverty. In his landmark work The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844, Friedrich Engels described our Salford neighbourhood as follows:

“…cleanliness and comfort are impossible… [A] mass of courts and alleys are to be found in the worst possible state [and] vie with the dwellings of the Old Town in filth and overcrowding.”

Further extensions to the Islington Mill site were subsequently added over the years, including a second mill by 1830 occupying the west part of the site (still extant and now known as New Islington Mill), stables on the courtyard, a lift, a warehouse, and the external engine house to replace the original internal one.

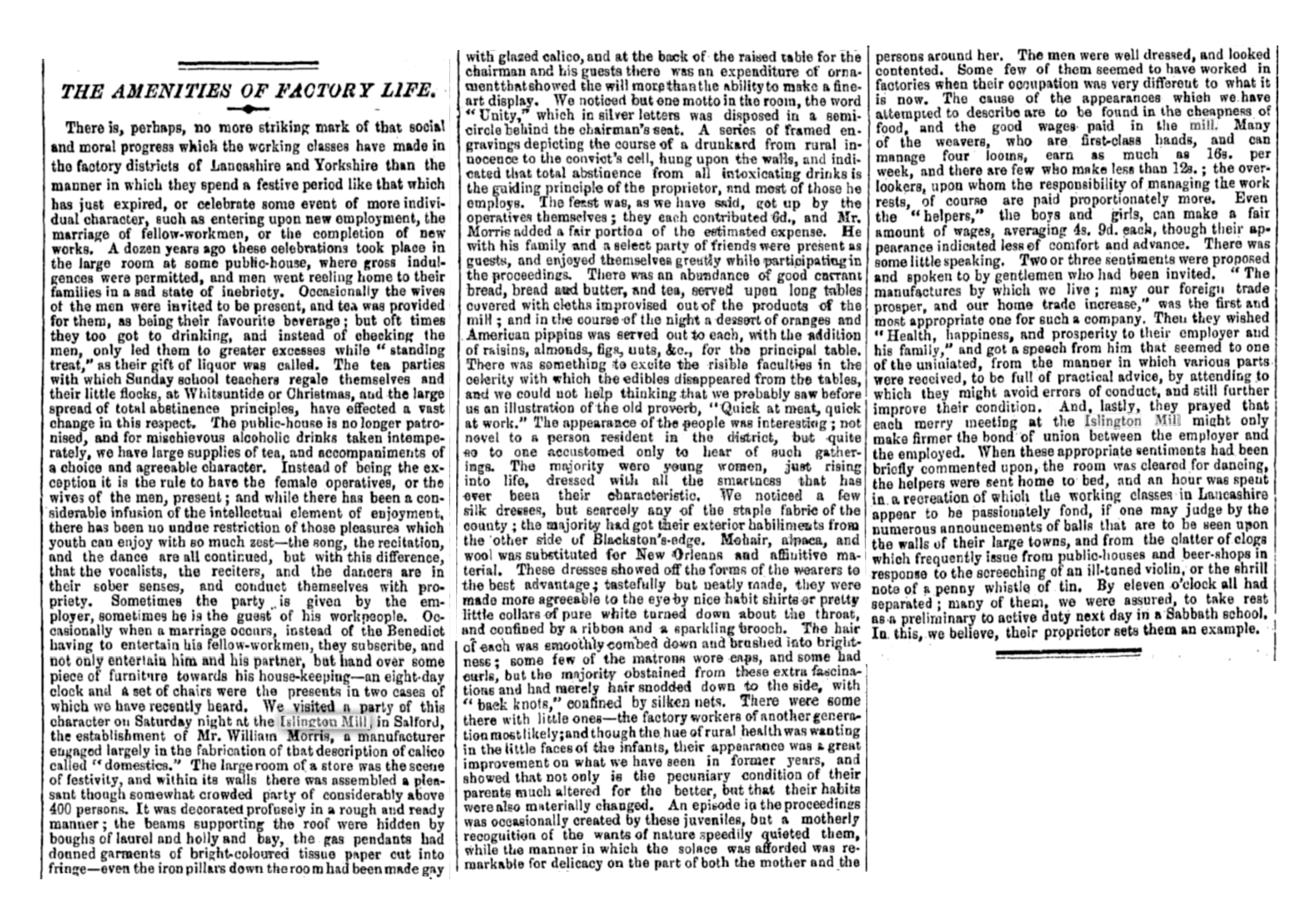

1853: Party at Islington Mill

In 1853 the Morning Chronicle reported on a festive party held by William Morris at his establishment Islington Mill. Over 400 people attended and it was decorated in a “rough and ready” manner with the beams supporting the roof “hidden by laurel and holly and bay” and “bright coloured tissue paper cut into fringe”. The majority of the party attendees were young women.

“We noticed a few silk dresses, but scarcely any of the staple fabric of the county; the majority had got their exterior habiliments from the other side of Blackson’s edge. Mohair, alpaca, and wool was substituted for New Orleans and affuitive material. These dresses showed off the forms of the wearers to the best advantage; tastefully but neatly made, they were made more agreeable to the eye by nice habit shirts or pretty little collars of pure white turned down about the throat, and confined by a ribbon and a sparkling brooch”

– Morning Chronicle, 1853

Remaining on the Islington Mill site for over 33 years (except a few years away to run a chippy!), Gladys worked in the building for most of her life and was here during a period of massive social change.

Gladys supervised the machinists, then when the Mill transformed into a dress shop she stayed on and worked her way up to the position of manager.

Early 1960s:

Islington Mill Fashions

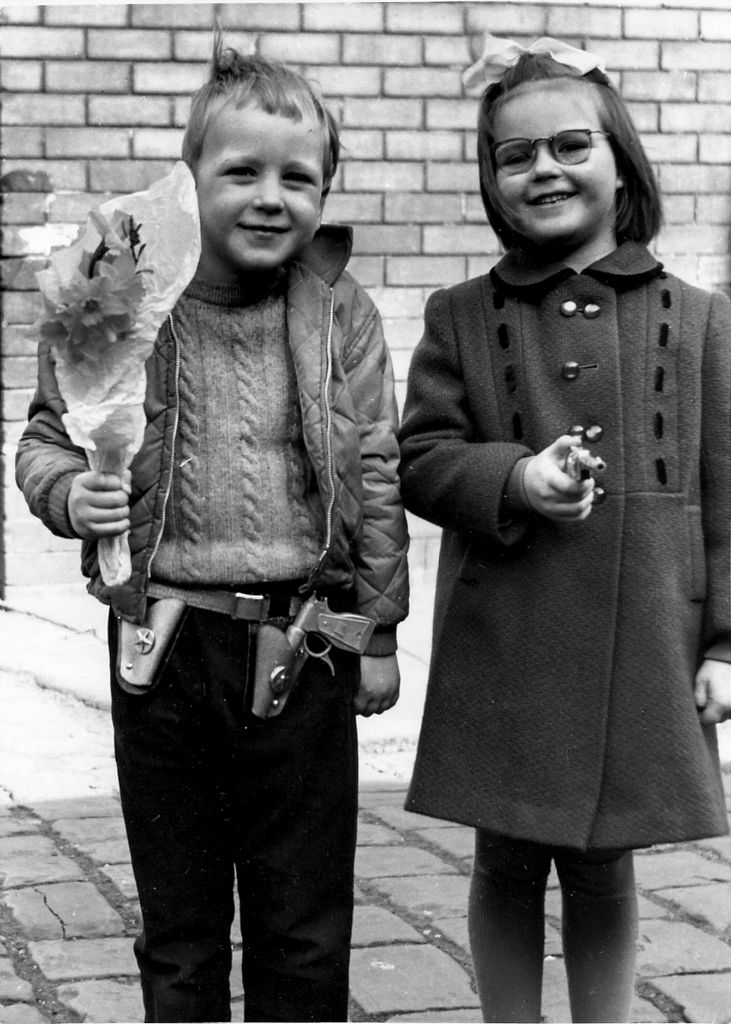

Instead of having garments made by machinists on site, Maurice and Emmanuel Sylvester adapted their business model and began importing clothes from Germany to sell to the people of Salford and beyond in the early 1960s.

Many local Salfordians still remember buying their coats from Islington Mill throughout the 60s and 70s. According to a local woman who had a Saturday job at the store, it was frequented by Coronation Street stars and even Manchester United manager Sir Matt Busby.

This wonderful photograph was sent in by Julie Hetherington and shows one of the coats sold from Islington Mill Fashions. We would love to see more photos that people may have of the clothes they bought from the Mill!

1976–1981:

AMEK Technology Group

AMEK Technology Group first came to Islington Mill in 1976, where they occupied the second floor of the main building and remained here until 1981 when they moved over to New Islington Mill. Founded by Nick Franks and Graham Langley, AMEK manufactured audio mixing consoles for the recording studio, live sound and broadcast industries.

AMEK and sub-brand Total Audio Concepts eventually came to have a very high-profile client list which included artists such as Bruce Springsteen, Genesis, Iron Maiden, Metallica, Queen, U2 and many others; and also most of the world’s major broadcasters, starting with the BBC.

AMEK was granted the Queen’s Award for Export in 1985, 1986 and 1987 and had sales in over 55 countries.

Photograph from the AMEK Online Museum.

1996:

Bill Campbell arrives, Islington Mill becomes a listed building

Two moments of important change for the Mill occurred in 1996. Firstly, the building was listed by English Heritage as a Grade II structure and was now subject to special protections. (Our building ID number is 471566 if you’d like to look us up).

Secondly, Bill Campbell, a young gay artist living in an adjacent tower block, noticed a ‘TO LET’ sign appear at the old mill across the way. Recently returned to Greater Manchester after studying fashion at Central St Martin’s, Bill rented the fourth floor of Islington Mill to use as his studio.

At this point much of the mill building, particularly the abandoned upper storeys, had been out of use since the 1960s. Bill soon began to share his new space with other artists and the first DIY art happenings (and parties) began to take place. In 1997, just nine months after Bill’s arrival, Islington Mill was put up for sale

2000:

New millennium:

Rachel Goodyear and

early years artists

Rachel Goodyear is an established visual artist and one of Islington Mill’s four Co-Directors. She is also one of the longest-established artists at Islington Mill. As part of our oral history research we interviewed Rachel about discovering Islington Mill and the impact it had on her, personally and creatively.

“It was like nothing I’d ever seen before…”

Rachel crosses the river and visits Islington Mill for the first time, feeling at once “a sense of possibility” from both place and people, and an alternate artistic route she hadn’t previously imagined. She meets a “really welcoming” Bill Campbell for the first time, learns about the Chapel Street Open, and sees artists already busily working away, including Susie MacMurray. “I feel invited here, I feel welcome here,” she recalls.

“One of the reasons I came back was that I’d heard there was a really good artist-led scene…”

After studying in Leeds, Rachel returns to Manchester “for a few months” where she overcomes her shyness and finds a community of artists. She discovers Castlefield Gallery and meets Director, Kwong Lee, from whom she first hears of a place called Islington Mill.

“It was a treasure trove of things and history …”

Rachel recalls the vastly different spaces inside the Mill, filled with detritus from the past, with a new layer of artistic creations beginning to appear, including a brilliant piece by Hilary Jack. Influenced by other Mill artists, Rachel rediscovers drawing as her core creative practice, exhibiting her drawing works for the first time. She also exhibits in the Chapel Street Open.

2001:

‘SHO 1’

“Art is anything that doesn’t fit easily in a paper bag…”

“Art is life…”

“Art is what you can get away with…”

Following from the Chapel Street Open in 2000, a new multi-venue arts festival emerged the following year, and counted Rachel Goodyear as part of its curatorial team.

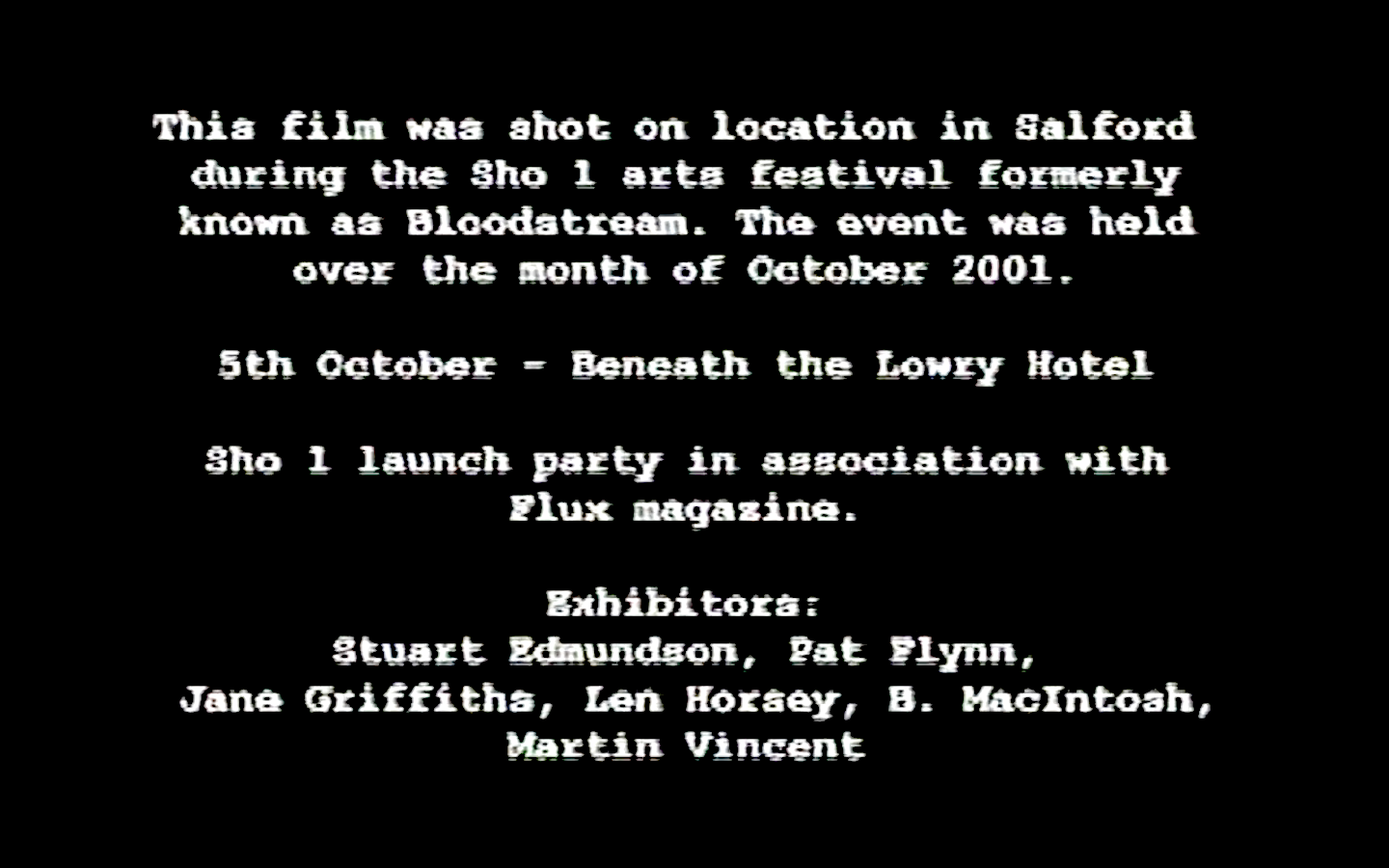

‘SHO 1’ is an exciting 12 minute documentary that depicts these events in October 2001 across a number of Chapel Street spaces, emanating from the main venue of Islington Mill.

The film – made by Barry Thomas and commissioned by the Chapel Street Regeneration Project – pinballs around the Mill, capturing detailed shots of work on show including a fashion show, sculpture, painting and installation. The painted line which the camera follows up the staircase, across floors and around doorframes can still be spotted in parts of the building today.

There is footage of open studios and other Mill interiors and exteriors, as well as other Salford and Chapel Street venues, including the Chapman Gallery at University of Salford, and Saint Philip’s Church (watch out for an electric guitar being played by a vibrator).

‘SHO 1’ by Barry Thomas

Other venues mentioned are Ordsall Hall and The Lowry, which at the time had been open less than a year. There are also many shots and fascinating vox pops with audience members.

Running throughout the film is the provocation, ‘What is art?’ which yields answers from the hilarious and rambling to the heartfelt and sublime. Some of the origins of Islington Mill are expanded upon by one of the interviewees but with several inaccuracies which our research will expand on at a future date. Even in 2001 the roots of Islington Mill were shrouded in mystery!

The SHO 1 model of a creative hub at Islington Mill with related events spilling up and down Chapel Street can easily be recognised as a prototype festival model for Sounds From The Other City which launched in 2005.

2007:

Islington Mill Art Academy

Islington Mill Art Academy (IMAA) was started in 2007 by Maurice Carlin. It is our free peer-led art school. It is open to anyone who wants to be an artist. Learning activity (workshops, crits, coaching, group residencies and projects) is shared and led by the energy and ideas of the current student-members. The Academy is not formally accredited; students choose to graduate when they feel ready to work more independently as artists.

2020:

National Lottery Heritage Fund

In January 2020 the National Lottery Heritage Fund announced that our funding bid was successful and that £746,000 was to be awarded to Islington Mill to complete our capital fundraising project of over £2 million.

This generous award from the National Lottery Heritage Fund allows for our building programme to commence. That means a new roof, complete weather-proofing of our structure, new entranceways, exterior lift to all floors, a fifth storey walkway, and new live/work/event spaces in a complete transformation of the 5th and 6th floors.

Most importantly of all it means our tenancy of this magnificent building is secured and there will be artists at Islington Mill for hundreds of years to come because of what we all did together in these years.